Happy Birthday, Zora Neale Hurston!

“Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonished me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”

—Zora Neale Hurston, How It Feels to be Colored Me, 1928

Perhaps the most accurate sentence a person has written about Zora Neale Hurston comes from an article about her life in The Bitter Southerner, an online magazine that aims to “uncover the American South in all its truth and complexity”:

“Myths ferried Zora Neale Hurston through life. And long after her death in 1960, they coursed through her work like a stream. But at times, it seemed those very myths hung over her like a constellation made up of stars she’d arranged herself.”

Zora Neale Hurston was born on January 7, 1901, (according to the epitaph which was engraved nearly a decade after her death by author Alice Walker) in Eatonville, Florida. Or 1902. Or 1903. The year changed, depending on who you asked because it changed depending on who she told. But she was always born in Eatonville, Florida.

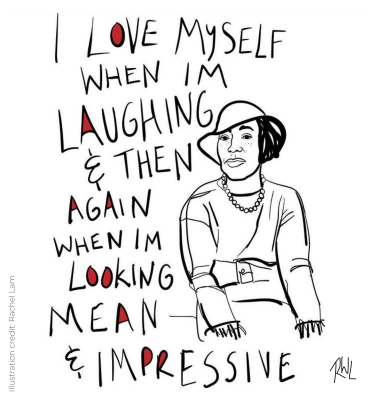

Rachel Lam (Anidiguwagi, enrolled Cherokee Nation)

Rachel Lam (Anidiguwagi, enrolled Cherokee Nation) Portrait of Zora Neale Hurston. (Rachel Lam [Anidiguwagi, enrolled Cherokee Nation])

As Michael Adno wrote in the Bitter Southerner piece, Hurston’s life was indeed “ferried” by myths. Though her name is probably best known for a novel taught across the country in many schools (Their Eyes Were Watching God), she died in “obscurity and poverty” (as phrased in her Associated Press obituary) with an unmarked grave, her works were all but almost lost when, upon her death in 1960, a janitor was ordered to burn everything.

Fortunately, Deputy Patrick Duval, who had known Hurston personally and was aware of her importance, happened across the burning, intervened, and saved the half-burnt lot from full destruction.

However, it wasn’t until Alice Walker, known for her novel The Color Purple, went down South in the 1970s (a decade after Hurston’s death) and pretended to be Hurston’s niece, that her life would begin to come back to the land of the living. Along with literary scholar Charlotte D. Hunt, Walker discovered an unmarked grave that they believed belonged to Hurston. She had it marked with the epitaph:

ZORA NEALE HURSTON / A GENIUS OF THE SOUTH / NOVELIST FOLKLORIST / ANTHROPOLOGIST / 1901*–1960

*As noted above, she was born in 1891.

In 1975, Walker would publish “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” in Ms. Magazine and launched a resurgence of interest in Hurston and her works. She not only inspired Walker but countless others including such names (and pillars of Black American literature) like Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison. Her works, which portrayed racial struggles in the American South, focused on the Black American experience—particularly that of the Black American woman.

“There is enough self-love in that one book — love of community, culture, traditions — to restore a world,” Walker would later write about Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. “Or create a new one.”

Yet self-love is almost not enough to convey the power of Hurston’s writing. In her 1928 book How It Feels to be Colored Me, Hurston penned:

“Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonished me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”

It is this self-love, this confidence, this preservation (and indeed love) of “community, culture, traditions” that propelled Hurston to become a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance. She wrote over 50 short stories, essays, and plays before time tried to all but erase her from our memory.

Hurston’s impact on American literature is beyond what most people may even realize — it is likely no coincidence that Zora, a webpage on Medium (an online publishing platform), is dedicated to “celebrating and centering the experiences of women of color.”

Further resources:

- The Official Website of Zora Neale Hurston

- “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” by Alice Walker for Ms. Magazine

- “The Sum of Life: Zora Neale Hurston” by Michael Adno for The Bitter Southerner

EchoX is starting a new series called EchoX’s Birthdays, where we acknowledge and celebrate the life, accomplishments, and impacts various people had on their communities (and beyond). As part of this series, we are commissioning artists to create portraits to accompany these articles on our website and on social media.

If you are interested in signing up to be on our commissions’ list (or if you have a suggestion of someone who should be in our Birthdays Series, please email voices@echox.org.

Our Northwest ethnic cultural communities have stories to tell and we need your support to amplify them! Donate $5 or $10 to help us continue raising the visibility of Northwest cultural community organizations and members. Follow us on social media or sign up for our mailing list to stay up to date on the latest in the Northwest.