The Pressure to Excel — The East Asian Experience With Academic Validation

*Disclaimer: In order to protect the privacy of the individuals interviewed for this article, names, and identifying details have been changed.

Grades are important to many students, but due to cultural pressures, Asian American students in particular can be more susceptible to basing their self-esteem on academic validation.

“[Academics] are ingrained in our culture,” says Chloe,* an Asian American student at the University of Washington. “It’s really important, especially for my mom. I would take home a 97% and she’ll be like, where the other 3% go?”

Academic validation, or basing one’s self-esteem on academic achievement, often creates negative stereotypes and has negative effects on a students well-being.

“Academic validation can be really good, it can be positive, if you have a healthy relationship with school and your grades,” says Abigail,* a high school counselor at the Mukilteo School District. “But academic validation can get really toxic when you stake your entire well-being and your confidence on whether or not you’re getting the right classes, or you’re following one particular pathway to your goals.”

Placing importance on grades and placing your importance on grades are two entirely different matters, with the latter having a far-reaching impact on the lives of the students. Asian American students, in many cases, face more unique challenges that have the potential to affect their academic performance, compared to their other American counterparts.

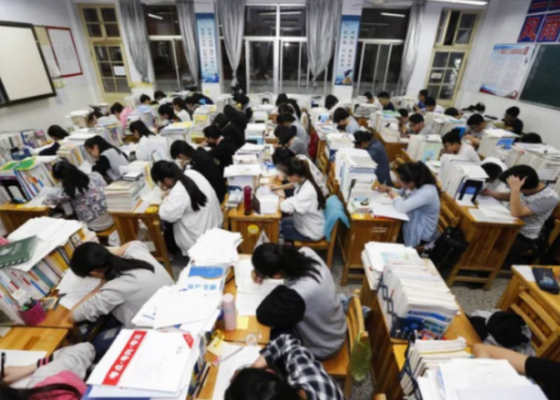

Students in China study for the Gaokao. (ChinaImages/Deposit Photos)

Students in China study for the Gaokao. (ChinaImages/Deposit Photos) Academics have long been a critical aspect of Asian American families and societies. The intense focus on academic achievement has been deeply ingrained into the cultural fabric of countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, where many East Asian American students’ families originate—and develop their belief in the importance of education. For most Asian students, there is only one path to success: study and education.

“[Students in Asia have] a mentality of a first tier,” Professor Hwy-Chang Moon, Dean of Seoul National University’s Graduate School of International Studies, told USA Today. “You have to be first-rate, otherwise you may not be able to survive.”

In countries like China and South Korea, students base their entire lives on one test. Referred to as “pressure-cooker” exams, the Chinese Gaokao and Korean Suneung are grueling tests, often spanning nine hours to complete. Students often spend the entirety of their high school career studying for these exams in hopes of getting into a good college and finding a successful job.

While Asian Americans don’t need to deal with the stress of the Gaokao or Suneung, this doesn’t mean they are free from the constant stresses of school. Since many students are either first-generation or children of first-generation immigrants, those cultural and academic habits are not lost when they move countries.

In addition to academic stress, there’s another layer of pressure for the children of immigrants—they don’t want to disappoint their parents. This can make school feel even more daunting as they strive to meet their family’s expectations while also trying to succeed in a new academic environment.

“[This comes] from wanting to prove that [my parents] did all this for a good cause,” expresses Anna*, an Asian American student at the University of Washington.

University of Washington campus at night. (Courtesy of Derek Zhu)

University of Washington campus at night. (Courtesy of Derek Zhu) For many Asian American students, their parents’ hard work and sacrifice in coming to a new country is a significant driving force behind their desire to succeed in school. But the pressure to excel can have both positive and negative effects. On one hand, it pushes them to work harder and strive for excellence in an effort to make a better life for themselves. But on the other, when students fail to meet the expectations set by themselves and their parents, it can be incredibly challenging to shake off feelings of failure and disappointment. It’s no secret that parents often want the best for their children. But despite their good intentions, the burden to excel can still generate strong feelings of inadequacy.

The pressure to excel academically in Asian American families has also inadvertently contributed to the “model minority” stereotype widely known today. On the surface, the stereotype appears to be positive, portraying Asian Americans as smart, hardworking, and high-achieving individuals.

“I was always expected to know things because I was Asian,” says Chloe. “It was kind of annoying because I know the information because I studied, not because I’m Asian.”

The stereotype not only places more peer pressure on Asian American students to perform well academically but also undermines their individual abilities and hard work.

In instances where a student doesn’t reach their expectations for a grade or class, it can trigger feelings of not being enough and imposter syndrome.

University of Washington Quad at night. (Courtesy of Derek Zhu)

University of Washington Quad at night. (Courtesy of Derek Zhu) “Honestly, I hate to say it,” states Anna. “But it totally crushes my self-esteem. It’s a huge part of my self-worth.”

This feeling is both valid and common among students, but it’s important to remember that there is a life beyond academics.

“Success isn’t just about your grades,” shares Abigail, “It’s about your resilience, it’s about your competence. It’s about your ability to deal with disappointment and failure. Those are all things that help dictate your ability to be successful.”

This line of thinking is supported by a study done by Nobel Prize winner James Heckman, who found personality to be a better predictor of success than grades.

Though sounding simple in theory, separating your self-worth from your academic achievements is easier said than done.

“Generally speaking, I don’t think it’s an accurate measure of intelligence,” says Anna. “[But] I can’t practice what I preach because I have such a toxic mindset about academic validation. […] When it comes to other people, I’ll tell them that a grade doesn’t define who you are or your abilities or anything.”

When you start believing your worth correlates with your academic achievements, it becomes easy to end up pushing yourself too hard. Some might feel the need to constantly prove themselves, creating more pressure and stress. Students usually don’t realize they’ve pushed themselves too hard until it’s too late. This lifestyle is not sustainable and could lead to burning out, potentially becoming a more severe problem like depression, anxiety, or even physical illness in some cases.

“You’re just mentally exhausted. You exerted all your energy into school, it’s just kind of impossible to get back up and get going [again],” Anna voices.

Recognizing it early on can help prevent it from escalating into more serious problems further on. Taking a step back to prioritize yourself again is crucial, and can include taking small breaks, doing the things you love, and staying healthy.

“Things like good and consistent sleep, time for yourself, hobbies, exercise, and nutrition are really number one,” Abigail says. “I know they’re cliche, but you really need them because the food you eat, the exercise you get, the sleep you get, these [all] greatly impact your ability to long-term deal with [stressors] and be able to access your full potential in the classroom.”

No one can go through life completely alone. Sometimes support from friends and family can be the proactive step needed to address your problems head-on.

“If someone you go to for help is not helping you to go to someone else. Try someone different. Don’t just give up because one person wasn’t helpful,” advises Abigail.

With school being a cause of a lot of students’ struggles, looking for support could help ease some of the pressures that come with the heavy load of expectations. Finding the fine balance between mental and academics early on could benefit students in the long run, developing healthy stress management skills.

“I wish I knew a setback doesn’t define your worth, and getting a bad grade doesn’t mean you are a failure for the rest of your life,” Anna recalls.

Chloe shares the same sentiment: “Grades don’t define who you are. Find projects and hobbies outside of school that give you passion to work for what you want, not what school wants.”

Academics don’t define a person’s worth, everyone has their own unique qualities and strengths. You are more than a letter on a report card.

Emily is a high school student at Kamiak High School. She was a fellow in the 2023 pilot Story Gathering Workshop, a program that gave twelve students the opportunity to write and publish an article for our news outlet, Voices.

Our Northwest ethnic cultural communities have stories to tell and we need your support to amplify them! Donate $5 or $10 to help us continue raising the visibility of Northwest cultural community organizations and members. Follow us on social media or sign up for our mailing list to stay up to date on the latest in the Northwest.